Getsemaní

Prensa de aceite. 2025

ES

Getsemaní. Prensa de olivo.

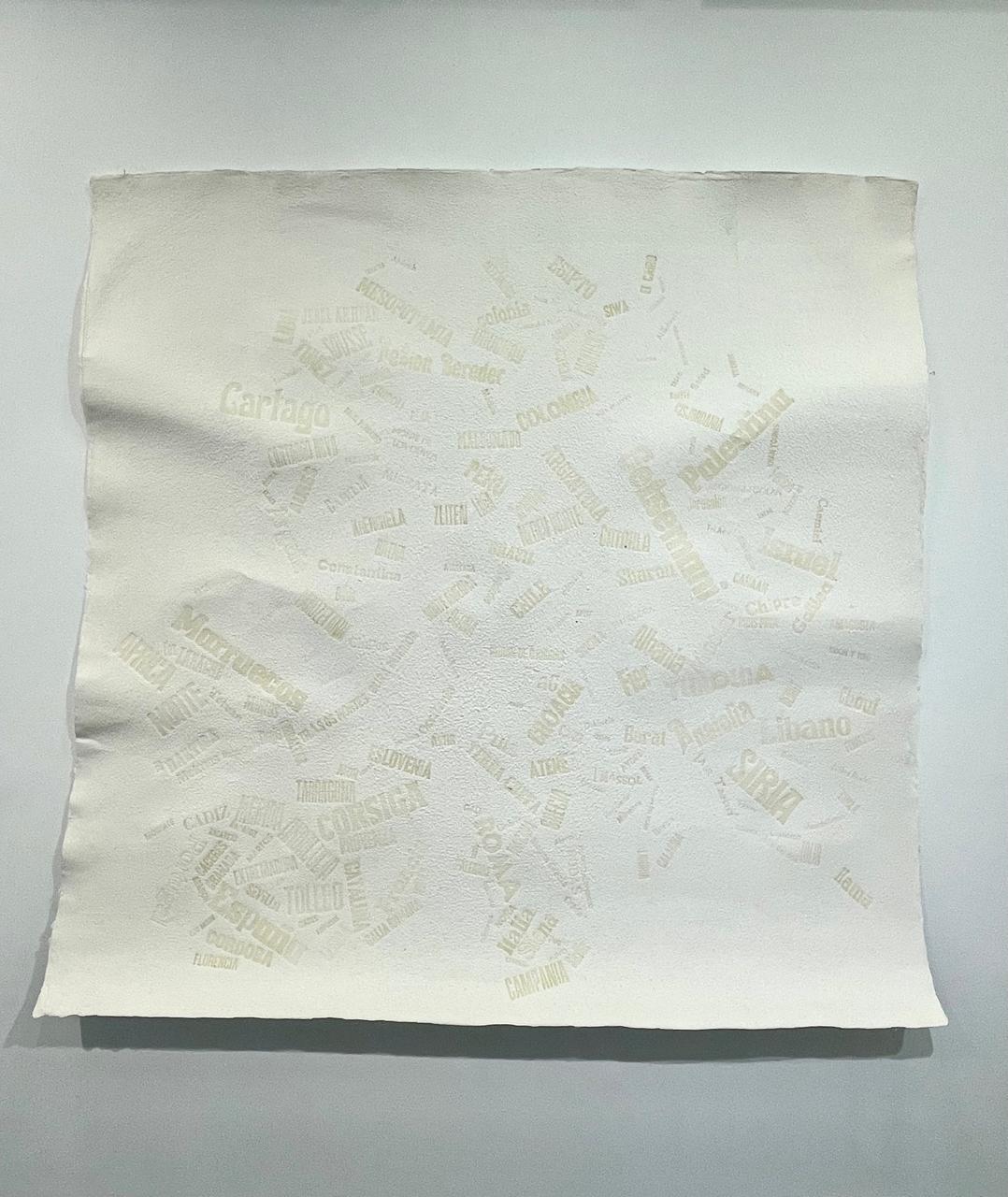

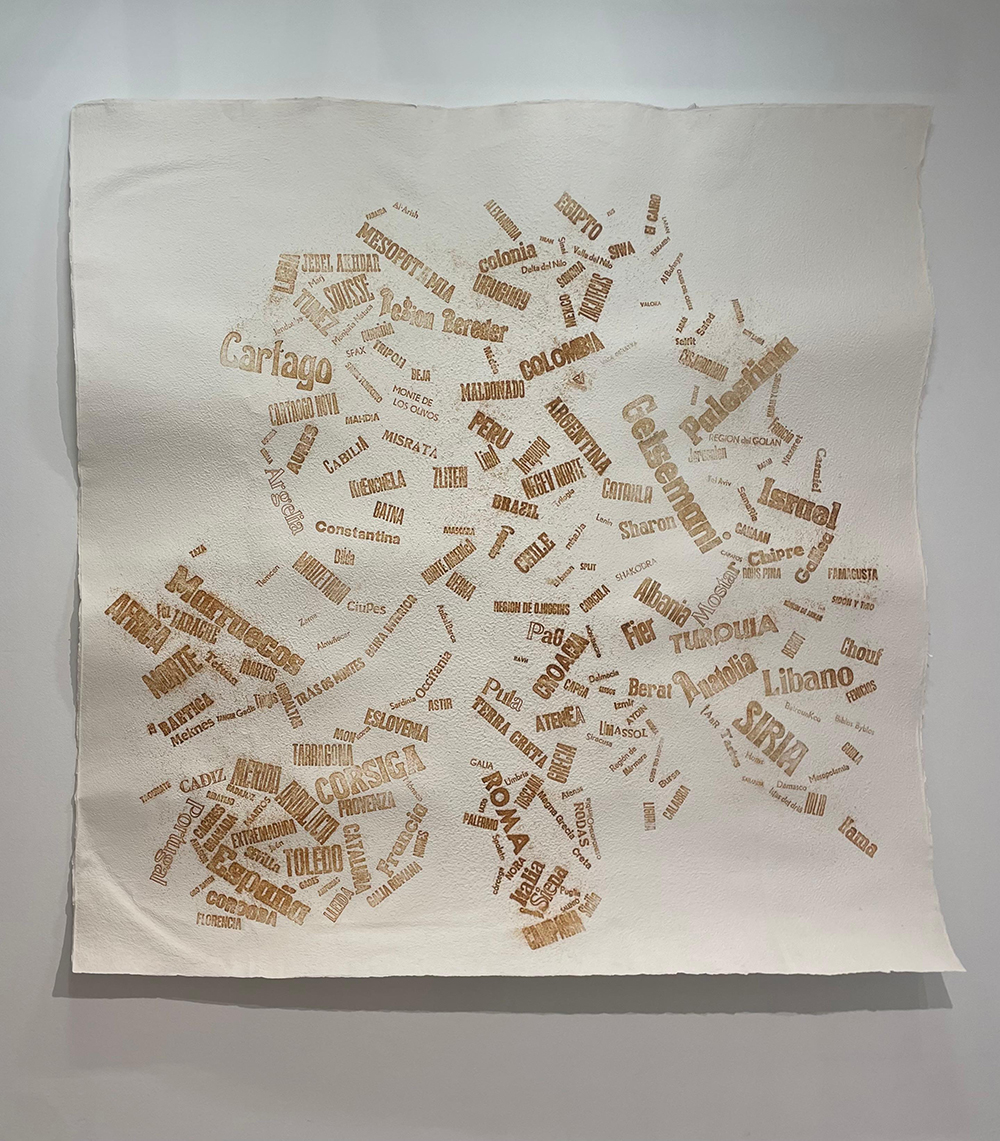

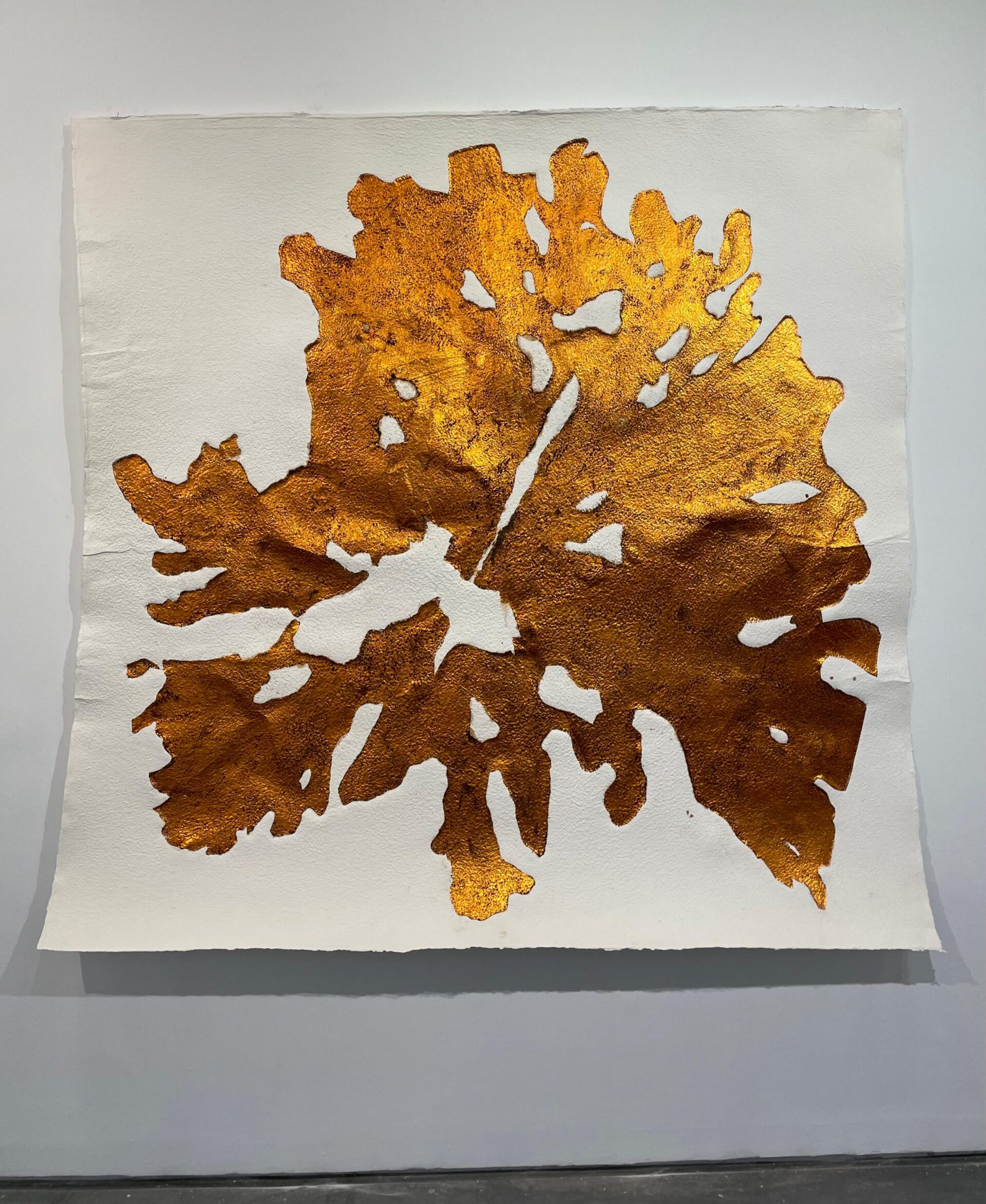

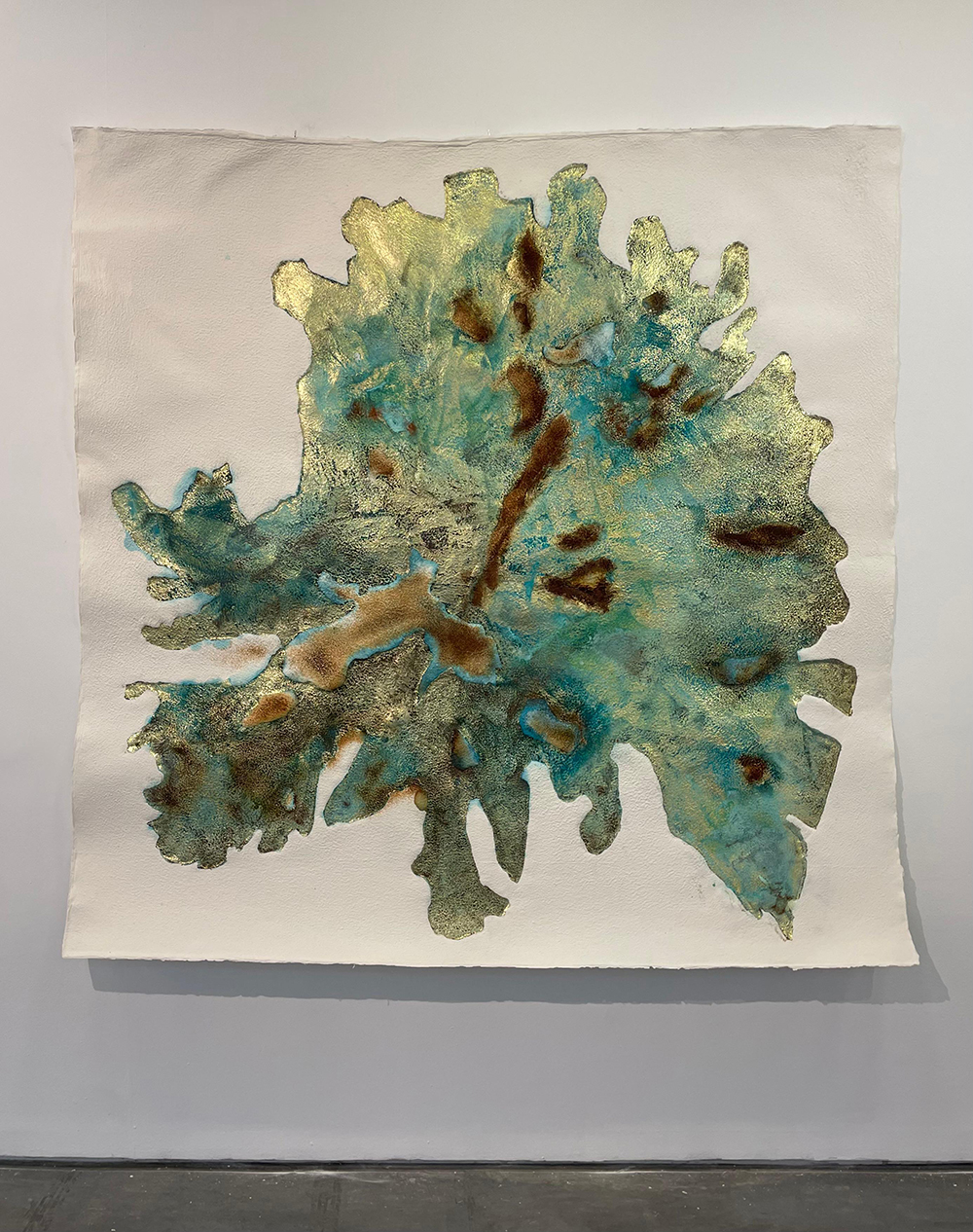

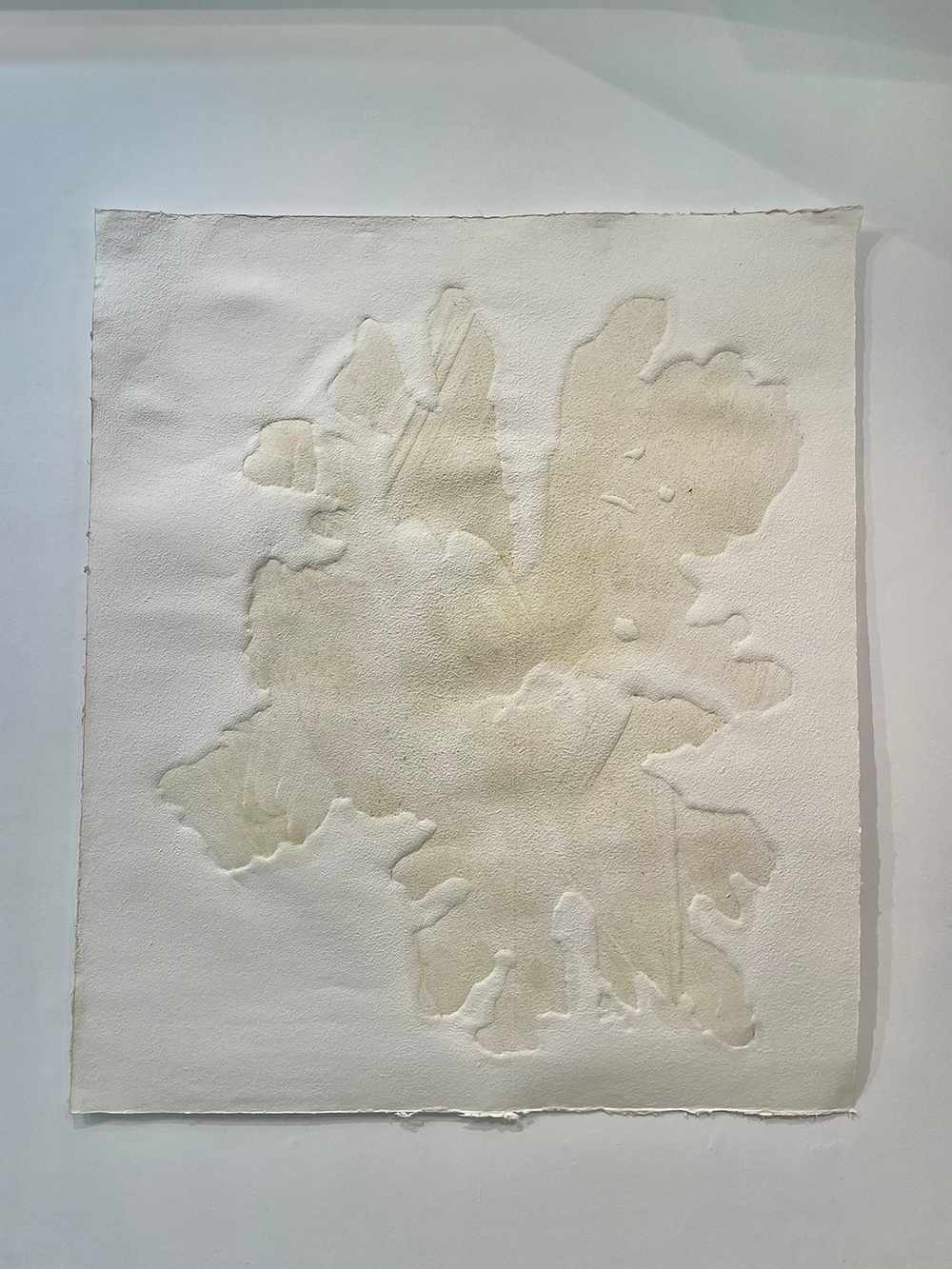

Lo más poderoso de estas obras es que fueron soñadas antes del encuentro. El papel, hecho a mano con algodón puro, fue producido en talleres de la sabana de Bogotá sin que el artista hubiera visto aún el árbol de olivo. Todo se pensó desde la distancia. Cada hoja fue un acto de espera. En ese mismo lugar se imprimieron los nombres de los territorios donde el olivo ha echado raíces a lo largo del tiempo, lugares antiguos, memorias que habitan la geografía de este sin que estuviera presente. Solo al llegar a Madrid se dio el encuentro. El olivo milenario recibió por fin la prensa, una prensa que imprime pero también acuña. Cada grabado lleva el nombre de una antigua moneda fenicia, como si en ellos también se imprimiera un valor, una historia, un símbolo de intercambio entre mundos. El olivo también ha sido eso, moneda de cambio, reserva sagrada, símbolo de riqueza y paz. Como en los antiguos tesoros la serie La Reserva guarda esta memoria. Cada impresión es única, como si cada hoja de papel reconociera el cuerpo que durante tanto tiempo había imaginado. Así se dio este cruce entre dos mundos.

Para Miler Lagos (n. 1973, Bogotá, Colombia) el árbol es el “testigo silencioso del paso del tiempo. Es el registrador de los cambios y los acontecimientos. Es la sabiduría, la perseverancia, la resistencia y la fluidez.” Los árboles son archivos vivos, fuerza y arraigo, cuerpos que sostienen la memoria del mundo sin imponerse sobre él. Sin embargo, el hombre, se ha concedido el derecho de interrumpir ese registro.

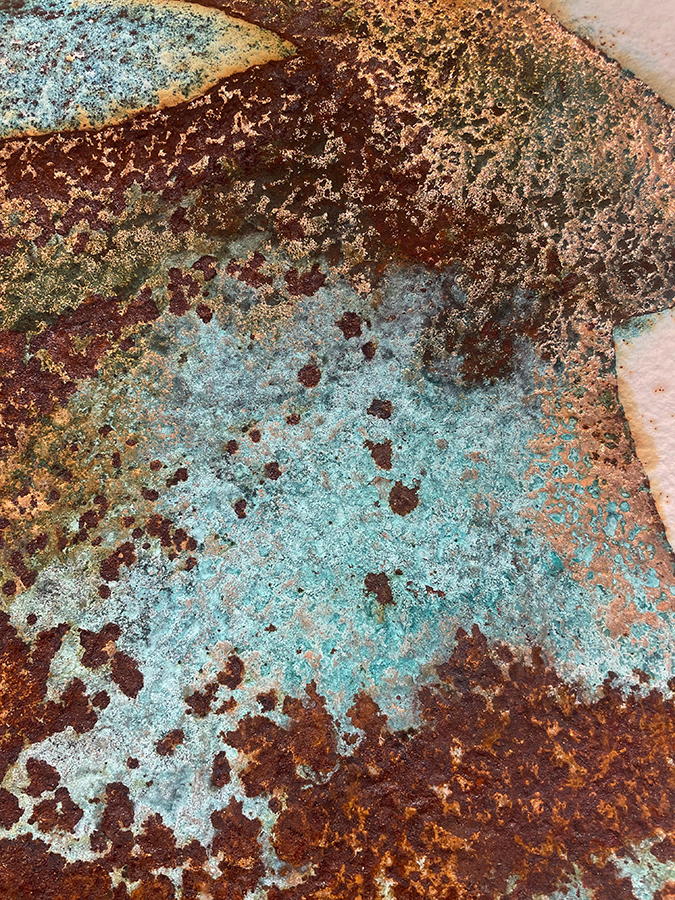

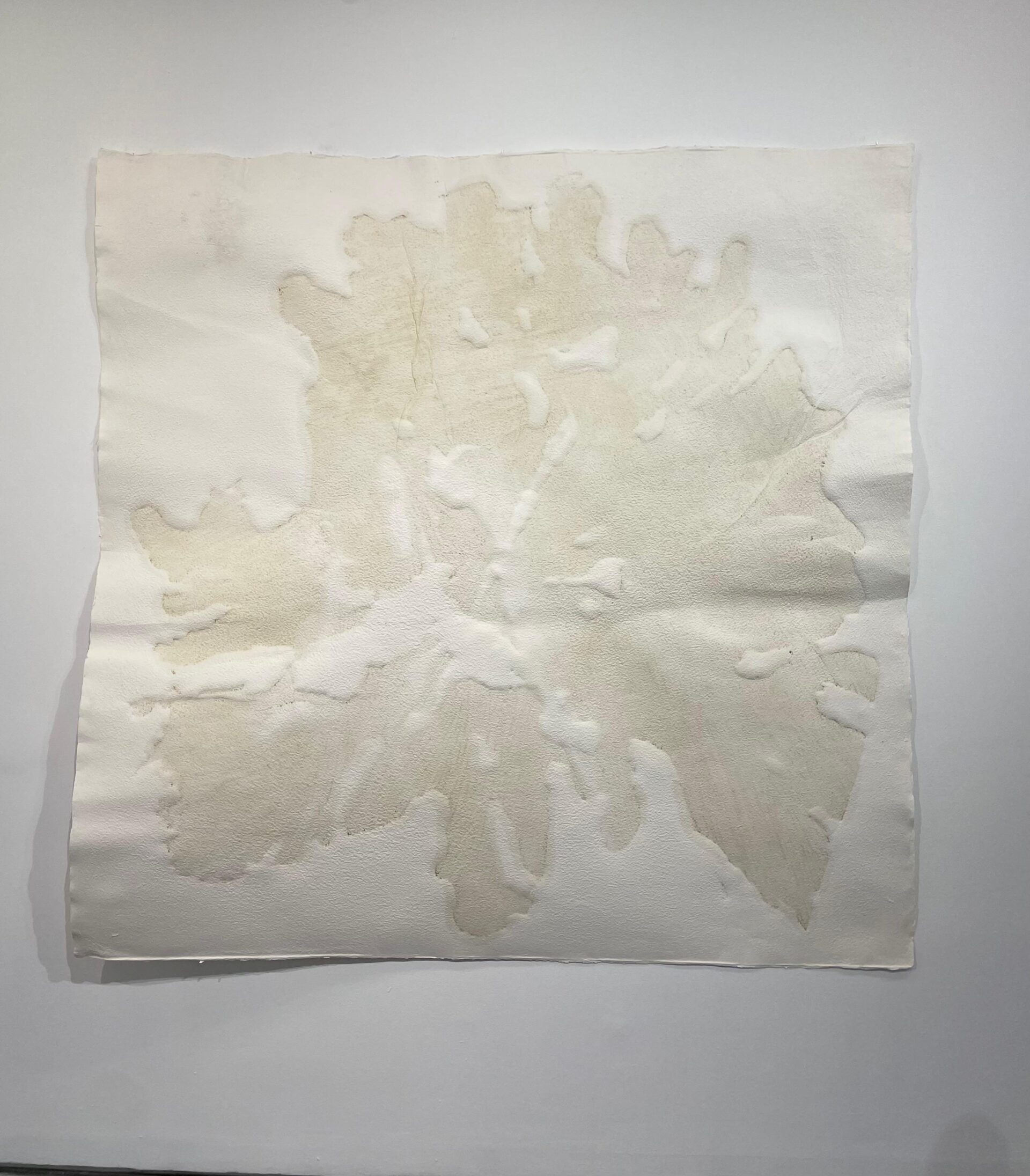

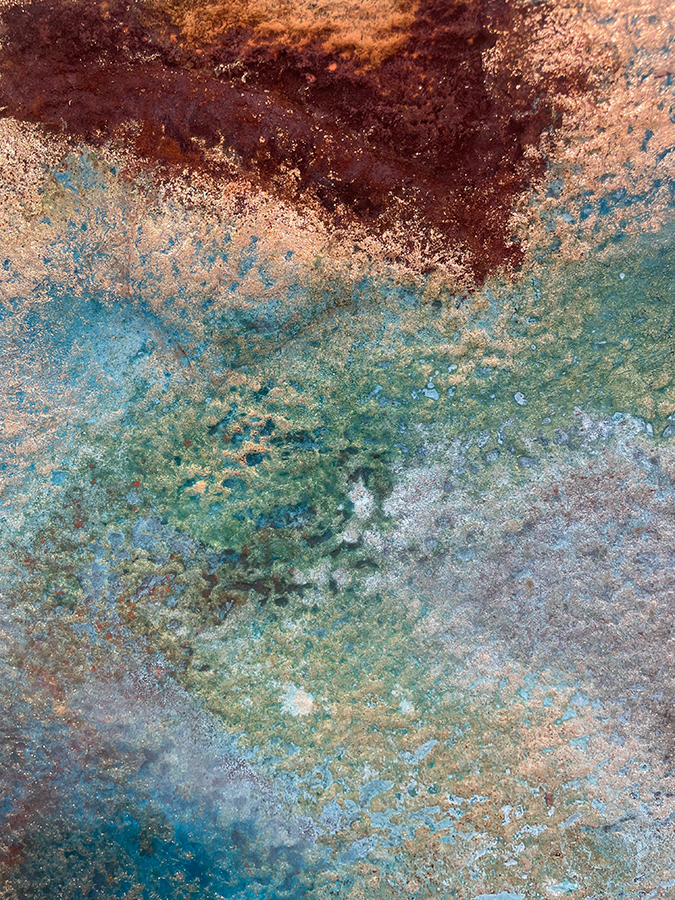

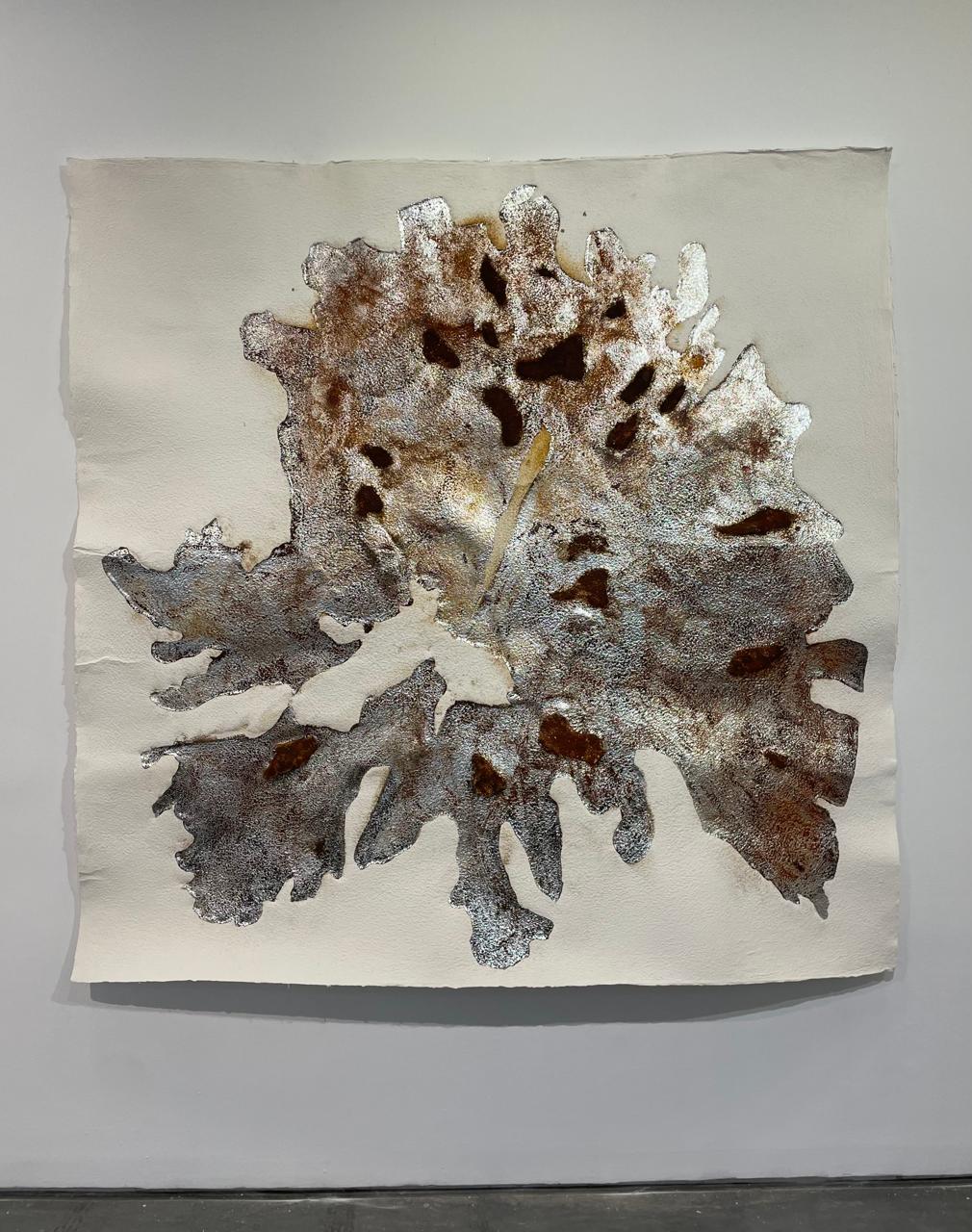

Getsemaní es el nombre de esta exposición, parte del proyecto La Reserva, una serie de grabados realizados con intaglio a partir de troncos cortados horizontalmente. La prensa imprime la huella del árbol y las obras capturan el vestigio del tiempo atravesado por la violencia de la máquina, permitiendo que la memoria continúe de otra manera. En cada impresión sobreviven la cicatriz de la motosierra y el óxido de la placa, y con ellos nace una nueva historia que el árbol comparte con la humanidad.

Miler Lagos expone la marca de la fractura, la cicatriz que interrumpe la memoria natural, un gesto de dominación que intenta controlar aquello que lo precede y lo sobrevivirá. La serie evoca agonía y resistencia, pero también la oportunidad de vivir nuevamente. Getsemaní significa prensa de aceite, el lugar donde las aceitunas eran trituradas para extraer su esencia. Aquí la prensa es metáfora de la violencia sobre la naturaleza y del acto de imprimir como herida, permanencia y contemplación. Como un sudario, cada obra es testimonio de lo que ha sido tocado, marcado para siempre. El árbol, que antes acumulaba historia en silencio, ahora se convierte en el testimonio visible de su propia extinción. Si el aceite de oliva fue símbolo de lo sagrado, ungüento de reyes y sacerdotes, la huella se vuelve marca de destrucción y a la vez posibilidad de reflexión.

En Madrid la serie presenta un caso particular: la impresión de un olivo milenario que murió en su traslado de Italia a España. Un árbol que resistió siglos de historia, pero que no sobrevivió al deseo humano de poseerlo. Impreso, su historia encuentra otra forma de vivir.

El olivo es raíz y frontera del Mediterráneo, patrimonio biológico e histórico protegido por leyes y por el saber campesino. Ha sido saqueado y venerado, desarraigado y resguardado. Acompañó imperios, rutas comerciales y rituales sagrados, cruzó mares y unió culturas. Sirvió de alimento, moneda y emblema de paz y resistencia. Esa tensión entre violencia y cuidado, pérdida y permanencia, habita estas obras.

Esta exposición es el vestigio de esa relación tóxica entre el hombre y la naturaleza. Como la prensa de aceite que desgarra el fruto para extraer su esencia, cada impresión registra el tiempo detenido, una herida que no cierra. La obra recuerda la paradoja: la humanidad protege lo que destruye y celebra lo que aniquila.

Pero lo que parecía el final se transforma en la insistencia de una presencia, en una forma de continuidad. En esa imagen impresa sobrevive no solo el árbol, sino el recorrido de una especie que acompañó el nacimiento de las civilizaciones mediterráneas. Desde las costas fenicias hasta el extremo occidental del Mare Nostrum, el olivo delineó el mapa cultural del mundo antiguo. La obra no solo recuerda lo que fue, sino abre un espacio para lo que aún perdura. Y es en esa permanencia donde el arte se vuelve espacio de resguardo, continuidad, posibilidad, celebración y archivo.

Juanita Escobar Bravo

EN

Getsemaní. Prensa de olivo.

The most powerful aspect of these works is that they were dreamt before the encounter. The paper, handmade from pure cotton, was produced in workshops on the savannah of Bogotá before the artist had even seen the olive tree. Everything was conceived from a distance. Each sheet was an act of waiting. In that same place, the names of the territories where the olive tree has taken root over time were printed—ancient places, memories that inhabit the geography of this tree without it being present. It was only upon arriving in Madrid that the encounter happened. The thousand-year-old olive tree was finally met by the press—a press that prints but also stamps. Each engraving bears the name of an ancient Phoenician coin, as if a value, a story, a symbol of exchange between worlds were also being imprinted. The olive tree has been that too: a medium of exchange, a sacred reserve, a symbol of wealth and peace. Like ancient treasures, the series La Reserva preserves this memory. Each print is unique, as if each sheet of paper recognized the body it had imagined for so long. That is how this crossing between two worlds came to be.

For Miler Lagos (b. 1973, Bogotá, Colombia), the tree is the “silent witness to the passage of time. It is the recorder of changes and events. It is wisdom, perseverance, resistance, and fluidity.” Trees are living archives, sources of strength and rootedness—bodies that sustain the world’s memory without imposing upon it. Yet humankind has claimed the right to interrupt that record. Getsemaní is the title of this exhibition, part of the project La Reserva, a series of intaglio prints made from horizontally cut tree trunks. The press captures the tree’s imprint, and the works preserve a trace of time marked by the violence of the machine, allowing memory to persist in a different form. Each print bears the scar of the chainsaw and the rust of the plate, and with them, a new story is born, one that the tree now shares with humanity.

Miler Lagos reveals the mark of fracture, the scar that interrupts natural memory: a gesture of domination aimed at controlling what came before us and what will outlive us. The series evokes agony and resilience, but also the chance for rebirth. Getsemaní means “oil press,” the place where olives were crushed to extract their essence. Here, the press becomes a metaphor for violence against nature and for the act of printing as wound, permanence, and contemplation.

Like a shroud, each work is a testimony to what has been touched, marked forever. The tree, once silently accumulating history, now becomes a visible testament to its own extinction. If olive oil was once a symbol of the sacred—an anointing balm for kings and priests, then the imprint becomes a mark of destruction and, simultaneously, a space for reflection.

Madrid, the series includes a particular case: the imprint of a thousand-year-old olive tree that died during its transport from Italy to Spain. A tree that withstood centuries of history, yet could not survive humanity’s desire to possess it. Through printing, its story finds a new way to live. The olive tree is both root and boundary of the Mediterranean, a biological and historical heritage protected by law and by rural knowledge. It has been plundered and revered, uprooted and safeguarded. It accompanied empires, trade routes, and sacred rituals; crossed seas and united cultures. It served as sustenance, currency, and an emblem of peace and resilience. That tension between violence and care, loss and permanence resides in these works.

This exhibition is the remnant of that toxic relationship between humanity and nature. Like the oil press that tears the fruit to extract its essence, each print records halted time -a wound that doesn’t heal. The work reminds us of the paradox: humanity protects what it destroys and celebrates what it annihilates. But what seemed like an end transforms into the insistence of a presence, a form of continuity. In that printed image, not only does the tree survive, but also the journey of a species that accompanied the birth of Mediterranean civilizations. From the Phoenician coasts to the western edge of the Mare Nostrum, the olive tree mapped the cultural landscape of the ancient world. The work does not merely recall what once was—it opens a space for what still endures. And it is in that endurance where art becomes a space of preservation, continuity, possibility, celebration, and archive.

Juanita Escobar Bravo

Documentación fotográfica del artista y la Galería Max Estrella

https://maxestrella.com/es/exhibition/getsemani-prensa-de-olivo/

Photographic documentation of the artist and Max Estrella Gallery